Escher’s impossible pleasures

What a wonderful coincidence that my first blog entry coincides with an exhibition of the ingenious Dutch graphic designer Maurits Cornelius Escher (1898-1972) and the great Japanese design studio Nendo, currently on at the NGV, Melbourne. This post will briefly focus on Escher’s body of work, namely the woodcuts and lithographs he created after 1936.

His tessellation drawings hugely contributed to the popularity of contemporary tessellations (repetitive, seamless, geometric patterns). I hope that you will share my enthusiasm for this brilliant and imaginative designer!

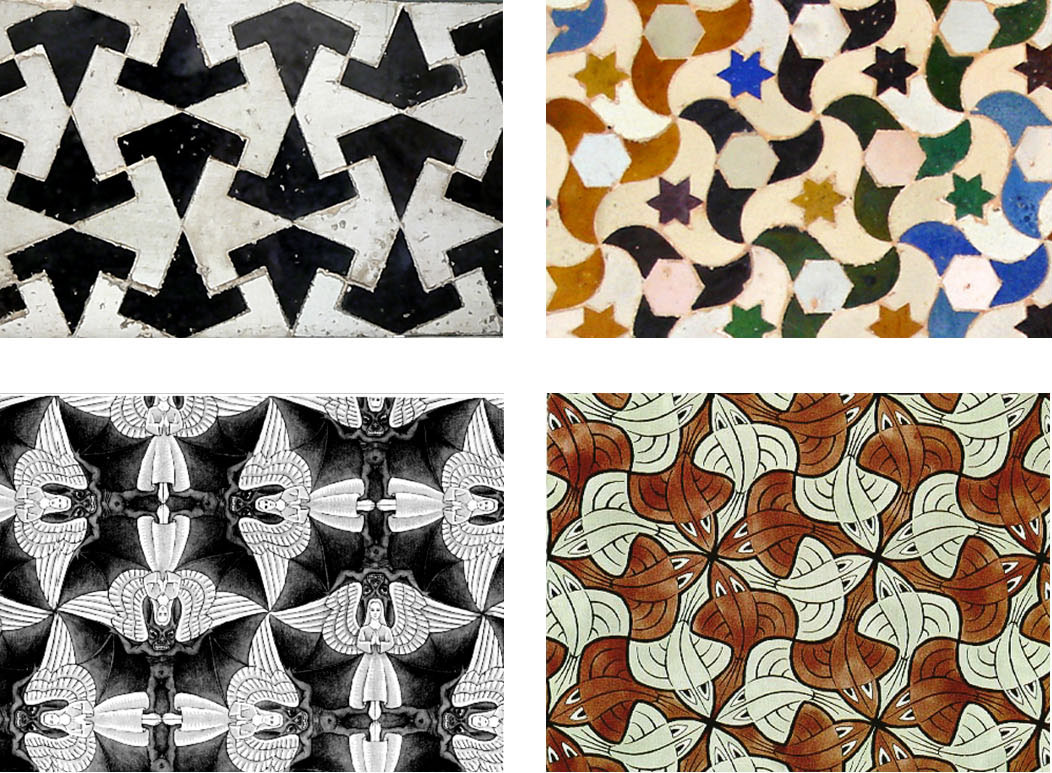

In 1936 Escher revisited the Spanish palaces Alhambra in Granada and the Mezquita in Córdoba to have a second look at the amazing Moorish patterned tiles and wall decorations, which he sketched on paper for future reference. Deeply influenced by these tessellations from the 14th century, Escher’s work started to change significantly. His motifs changed from mainly realistic Italian landscapes and villages (he lived in Italy for 13 years) to geometrical inspired and imaginative works of art. Escher became very interested in mathematical concepts such as symmetry and the regular division of the plane, which he used for creating tessellations by using geometric grids.

Images top left: Moorish tessellations, bottom left: Escher’s Angels and Devils (1960) and Fish (1964)

Whilst Islamic beliefs generally oppose the depiction of human and animal forms, Escher felt free to include living creatures in his designs. This enabled him to explore a broader range of patterns, meaning and playfulness.

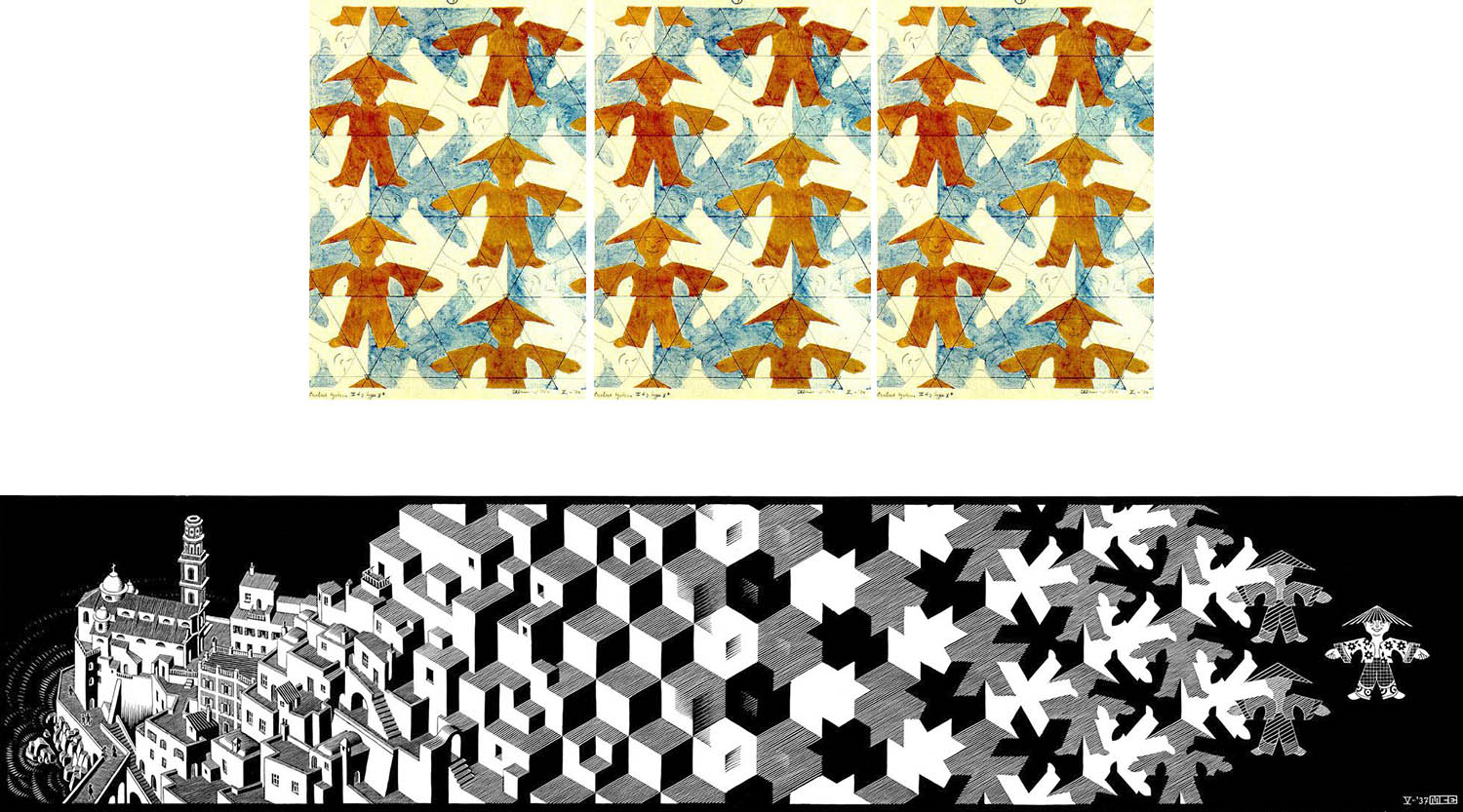

One of the early woodcuts he created during this time was Metamorphosis I (1937). Appropriately named, it morphs the Italian town Atrani into tessellated, geometric forms and ends up as a freestanding Chinese figure.

Images below: China Boy (1936), Metamorphosis I (1937), printed on two sheets

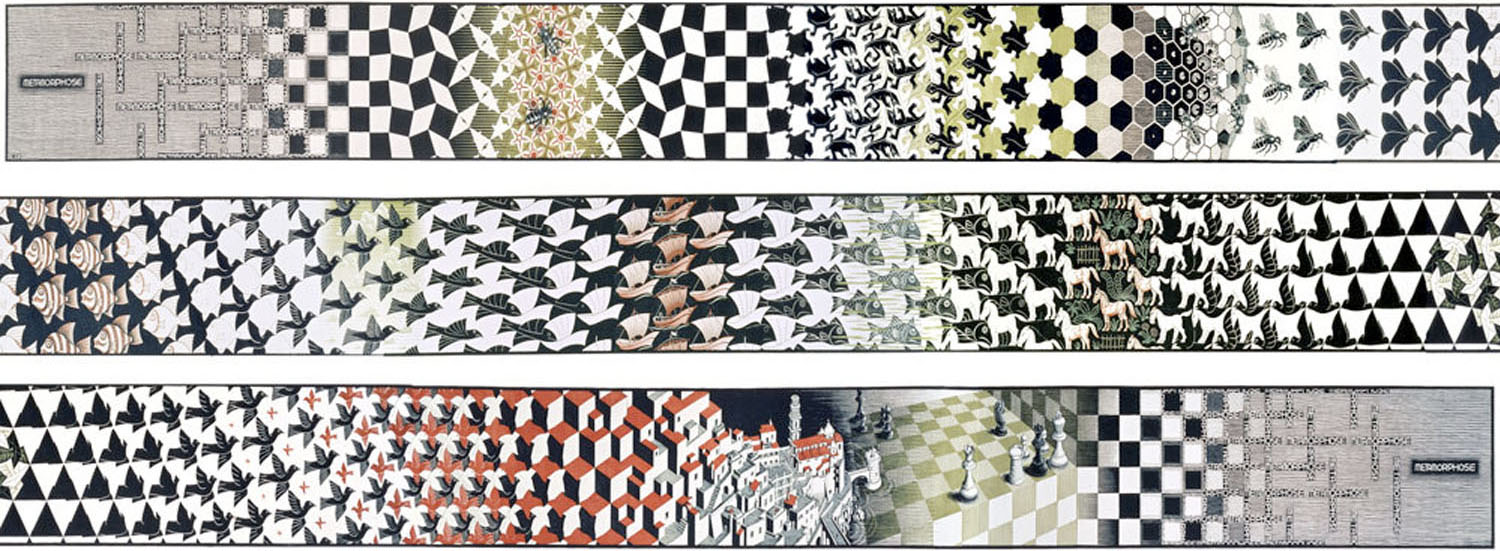

In 1940, Escher finished the more refined and larger Metamorphosis II (nearly four meters long), where tessellated caterpillars morph into butterflies and then turn into fish, change into mammals and finally transform into symbols of civilization such as architecture and chess to mark the end and the beginning in a never-ending cycle of creation and evolution.

Images below: Metamorphosis II printed from twenty blocks, on three combined sheets in one piece (1940), shown in three parts

Metamorphosis III is an extended version of Metamorphosis II and is very similar. It is also Escher’s longest print at nearly seven meters long! It can also be looped since the beginning and end are the same. That’s exactly the reason why The Palace in The Hague, Netherlands, exhibits this print in a custom made, round frame. A circular, endless frame is the perfect display to emphasize the indicated theme of eternity.

Circles, spirals and rings became more and more part of Escher’s work in one way or another. It would not have escaped Escher that the Islamic Moors considered the circle to be the most perfect geometric form, symbolizing infinity- obviously a theme he explored himself.

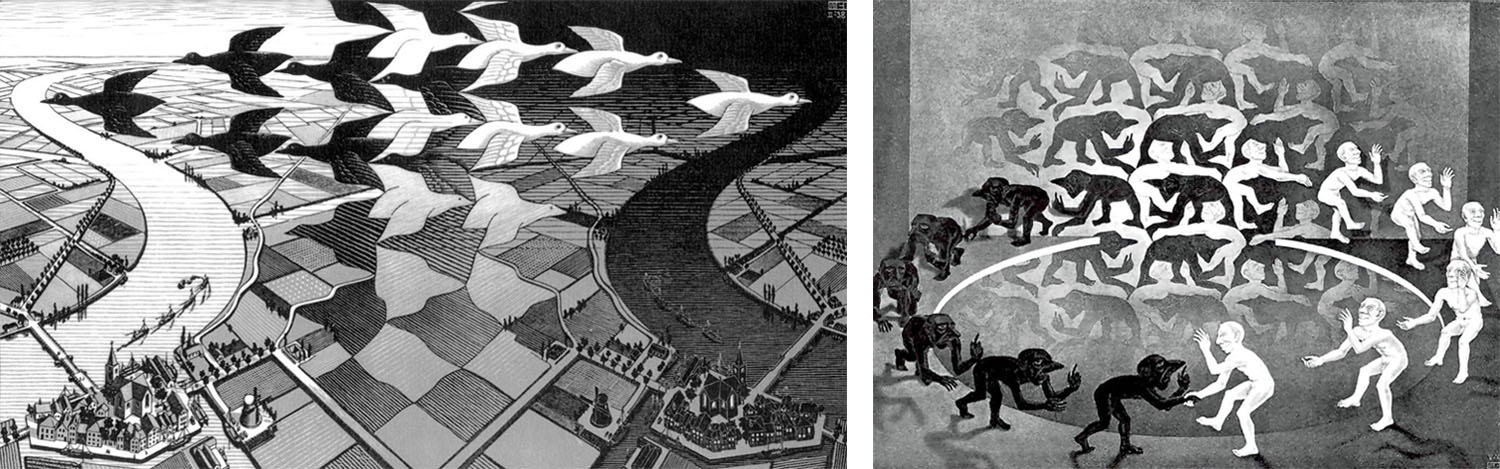

Escher was a master at creating optical illusions. Day and Night, one of his most popular woodcuts, plays with symmetry and mirrors the image on the opposite side (one side is as light as the day, the other as dark as night). The distinction between foreground and background is obliterated: the viewer can choose to see one or other set of shapes as foreground at will.

In his lithograph Encounter, the designer creates the illusion of three dimensional space: a group of men- half black, half white, walk in circles through a flat, two dimensional surface in the background, transforming into an imagined three dimensional world in the foreground. It’s our eyes and brain that fall for this optical trick! When the two groups- the optimists and pessimists, meet, they shake hands. A gesture of hope. Escher admits how much pleasure his creations give him: “It is for example, great fun deliberately to confuse two or three dimensions, the plane and space, or poke fun at gravity.”

Images below: left: Day and Night (1937), right: Encounter (1944)

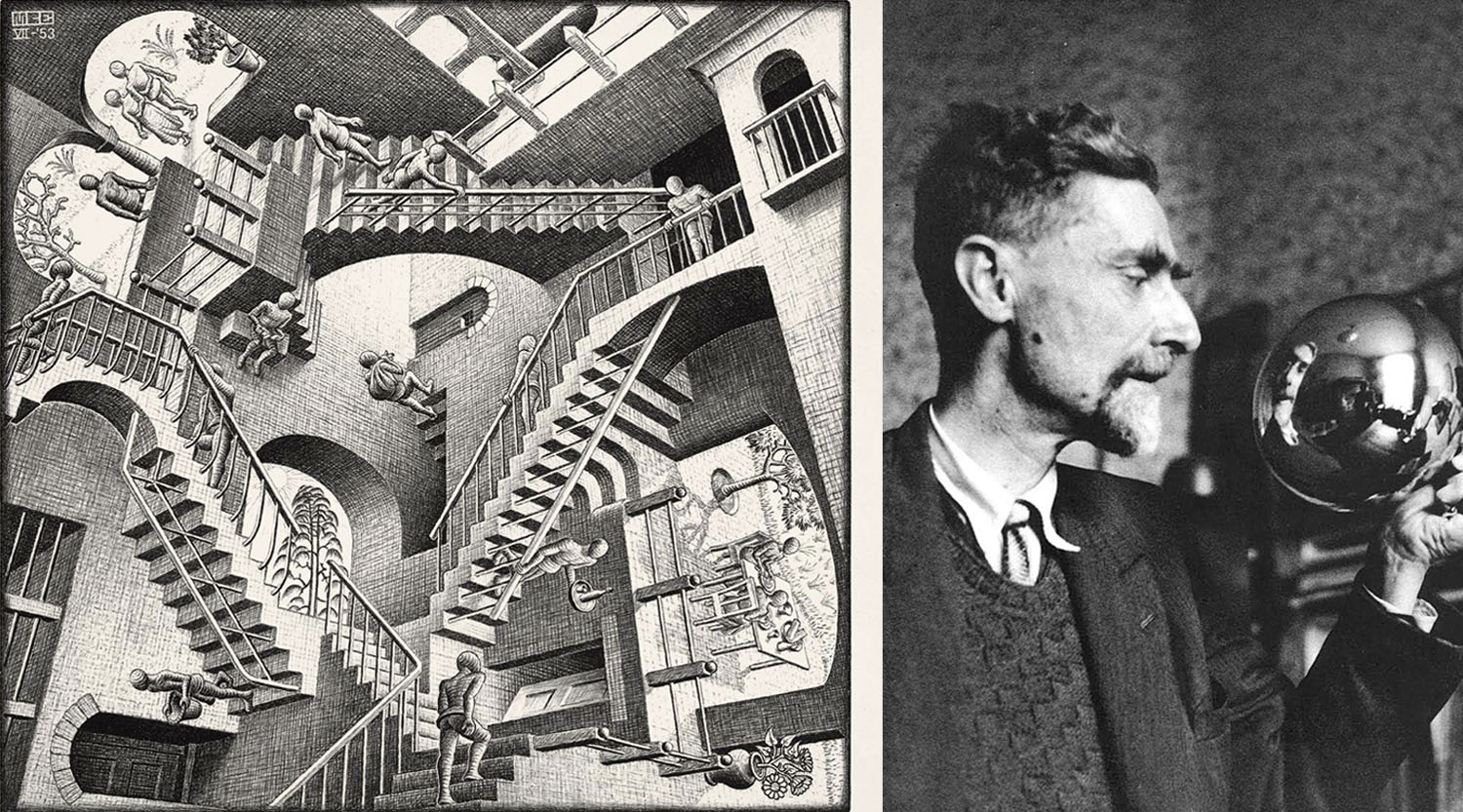

Escher definitely played games with gravity and perspective with his lithograph Relativity. There are three fields of gravity, each being orthogonal to the two others, forming an equilateral triangle in the middle. Despite designing this impossible scenario, the faceless figures walking up and down the staircases look perfectly normal (not distorted) in their gravity well, where he applied conventional physical laws. Remarkably, this illusion still works when their gravity spaces overlap! Escher explained: “If you want to express something impossible, you must keep to certain rules. The element of mystery to which you want to draw attention should be surrounded and veiled by a quite obvious, readily recognizable commonness.”

In 1954 Time magazine published (a second) interview with Escher, picturing Relativity, followed by a successful solo exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and the Whyte Gallery in Washington DC. Finally Escher received the recognition from the art world and public he well deserved. Until then, the mathematicians and scientists appreciated Escher’s work the most.

There were many more outstanding conundrums Escher created, showing impossible objects. He created his last work Snakes in 1969. I believe his most extraordinary skill was his curiosity and understanding of mathematical concepts, which he playfully combined with his exceptional designs- little alone his exquisite craftsmanship prior to any digital help a computer could offer.

Images below: right: Relativity (1953), left: Self portrait in spherical Mirror (1935)